[A few months ago, I

posted a quote from Traces from an interview with the Israeli writer and Holocaust survivor Aharon Appelfeld. I was very fortunate to hear him speak at Rimini yesterday and transcribe my notes below in first person. The title of the talk was "Bellezza e positività della vita" or "Beauty and Positivity of Life". He gave a very poetic and deliberate delivery, so I reproduce it as closely as possible.]

I refer to my generation, 1939'44, to children condemned to death. I was born in 1932 in Chernowitz in Eastern Europe which was Jewish and assimilated. My parents thought of themselves as European. My grandparents followed the Jewish commandments but without belief. They couldn't change their way of life. They had a sadness that was one of defeat.

The Holocaust buried us in suffering without distinction between believer and the alienated. Our suffering was physical as children, we had no soul-searching. For our parents, it was the loss of the world, their beliefs were overthrown. We were left only with naked Jewishness. It was an empty loss. Tens of thousands of Jews were separated from dear ones, deprived of everything, stigmatized with shame. Their heritage hemmed them in, blocked the path to full freedom. Together Jews from East and West were under an iron sky.

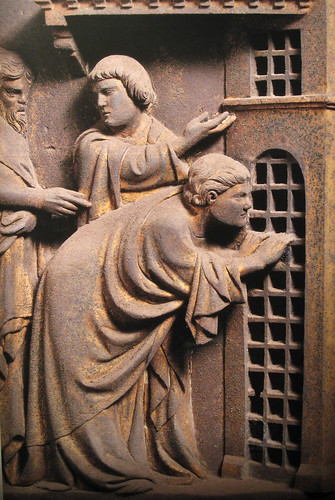

We were first exiled to the railroad station, with an enormous panic of hunger and crushed. We absorbed our parents' bitter silence before our separation. Our parents protected us until the last moment when they left us, as Moses' mother left her baby to the mercy of heaven.

Loneliness was our lot. Some were in the forest, others in monasteries and others lived with tyrannical peasants who treated us like beasts. We learned the secret of Judaism. It's better to hide it. Those with no parents were isolated from humanity and grew up like animals, cold and fearful. Judaism made us fair game. Without it, existence is more meager. That secret was the only shelter over our misery. We had images of our parents and our homes, our last refuge.

We lived with death as familiar but not ceasing to be afraid. Every encounter with death increased our fear. The promise to our parents was that we would look out for ourselves. This made us stronger than we were, when we wandered from forest to forest. We were not children but animals, who are lost in the dark thickets of forest. We learned to get food from trees, fire from stones and to reflect.

Why were we so persecuted? In the woods and on riverbanks, that question arose in all its nakedness. We thought it was our smell, our longer ears, our fear of darkness. If we overcame our flaws, no one would guess we were Jews. We did not know that was the old Jewish curst passed on.

In 1945 at the end of the war, I was 13. What to do, where to go? There was a sea of refugees flowing from place to place. We had a huge debt and didn't know where to put it down and get rid of it. A great catastrophe leaves us mute. What can we say about the death of one person, what more a heap of corpses. Speech was blocked, almost nothing was said. Speech is to serve existential needs, approaches the depths of the soul, is metaphysical. It is silent. The depths are full. Appropriate vessels were not raised up for what had accumulated.

I was orphaned not only from my parents, but their values and beliefs seemed naive and ridiculous in the face of the monstrous people who tortured us. What would our world be from now on? To go into the pit of cynicism, betray the beliefs of our parents, to betray the faith of my grandparents, inward religiosity, betraying my communist uncles who had sacrificed life for the redemption of humanity.

One dark evening, I realized the ghetto, camps, and forests would never leave me. I was lost in a world of lost values. I wrote the names of my parents, grandparents, uncles, cousins on a piece of cardboard. I wanted to make certain that they had existed, that the house I came from was not imaginary. By writing their names, I brought them to life. They rose and stood before my eyes.

I was no longer an orphan but a boy surrounded by loving people. I was so happy, I kept the paper in the lining of my coat, the key to my chest, precious secrets of the soul. If I felt lonely or oppressed, I took out the cardboard, the real names of the parents I had lost.

Writing opens a hidden world. The written word has the power to kindle imagination and illuminate the self. From cardboard to writing took a long time. Everything revealed in the war years crowded in me like a dark mass. I thouhgt of the ghetto, camp, forest. The images were no less horrible than reality. To avoid images, I would run out to cut myself off from them. The method worked only partially.

The past can't easily be separated from you. In 1946 in Palestine there was a pioneering spirit to create a new Jew, to shed the dread of the past. To turn toward the present and the future. The Jewish past was a curse to escape. The experience of the past seemed something shameful to be erased. Go and uproot from the soul everything experienced from five years to plant a pastoral idea. Forget about that significant part of life. People did that with a heavy price. A person without a past, as dreadful and shameful as it may be, is handicapped without connection to parents, grandparents. Without the values instilled by ancestors, it is like being a living body without a soul.

I wrote letters to my mother at night. It was a collection of trivial details about daily life. If they reached, her, they would make her happy. I did it eagerly night after night, which connected me to the world once mine. It did not act like a magic wand. Vexing questions plagued me. Who was I? What was I doing in an agricultural training program at the edge of the desert? Could I deny the spiritual world? My mother tongue was German. I heard it ag home until age 9. I learned Lithuanian and Prussian during the war. A few German words were sufficient to write to my mother letters full of mistakes.

In the afternoon I studied the Hebrew of daily life and the Bible. A young man from an assimilated, secular home recoils against religious books. I was not familiar with the Hebrew Bible and thought it full of angels and saints. What did they mean to me? A surprise awaited me. The patriarchs of the Bible were not saints but earthly, lively. There were treasures stored in the Bible. I decided to copy a chapter every day.

The Hebrew Bible deals not only with content but with form. The whole enchanted me. Biblical prose is simple, unembellished, lacking description, almost without adjectives. Like all ancient languages, it has a severity, a hard logic without sentimentality. I didnàt know severity suited my life experience. On the suffering of ghetto, camp, forest, it is impossible to lavish words. The greater the suffering, the more important it is to use few words. Pain refuses to be shaped by a language drunk with words.

In Biblical prose not speaking is as important as speech. Outward description is an illusion. We must strive to reach the inner kernel of soul. I didnàt internalize this easily or rapidly. The attraction for the sentimental or the noisy is almost natural. Biblical prose taught me to overcome the tendency the victim to regard himself as always right. Biblical prose taught me an objectivity to the superficiality of one-sidedness. In my life experience, egocentrism lurks in every corner.

Biblical narrative has no ideal people. These are flesh and blood with weaknesses. One is a womanizer, another vengeful, one sends a man to battle to die to take his wife, another is a villain. Primo Levi, on writing of Auschwitz, also wrote in very factual, dry language without rhetorical ornament, perhaps for the same reason.

It took great effort to acquire the Hebrew language. I made it my mother tongue and language to find me to my grandparents and great-grandparents and to learn about the character and destiny of the Jews. I read and copied the Bible. It included various experiences--poetry, prophecy, law, history, philosophy. I was charmed by narrative - people emerged, earthly people, but connected with heaven. There were no saints among them. But they knew in their souls they would not be without answers.

I read the Bible with devotion but it wasn't especially religious reading. I wanted to cling to the roots of language, to the primal experience of stories. It was a great joy, after years of struggling, I wrote a short story. The content was not biblical, but there was something of the poetics of the Bible in it.

Poetry is the assertion of strong people in the world, conscious and unconscious, people with us and those who have passed away. The longings, fears, grief and despair, marvelous moments. Life raises us beyond ourselves. We feel closeness to God. The Bible story has earnestness, like prayer, enclosed within it, it opens the heart in spiritual accounting. It does not lack humor, irony, penetrating criticism, ambiguity and sarcasm. The Biblical narrative is not didactic. It deals with good and evil, obligations, devotion, love for unworldly purposes and love for its own sake without preaching or idealization.

The Biblical narrative teaches that man is dust and ashes and created in God's image, two powerful feelings that traverse the length and breadth of the Bible story. Though heroes of the Bible forget, they are created in God's image. They behave like fatalists addicted to eat, drink and be merry for they will die. Abraham has closeness to God, is intimat ewith revelations, but has moments of weakness. He claims his wife is his sister for fear Pharoah will kill him. His treatment of his wife, of Hagar, is far from splendid.

The Bible shows human beings with lives and tribulations, with great questions on the purpose of our lives. It is great literature to be judged by what and by how. A true statement can sound false, banal, arrogant, garrulous if it doesn't find the correct form.

The story of the sacrifice of Isaac, what absurdity, cruelty, how can it be submitted without discussion? A short harrowing episode riddled with silence. What can the father say to the son? There is a short dialogue between them which is less revelatory than perplexing. Before the abyss our jaws are dropped. What lesson from this trial? Do everything God commands you, even if contrary to feelings of humanity. Any lesson from the episode, subject to a trial beyond comprehension, would be narrow-minded, dogmatic. Silence rather than speech characterizes it-the unsaid is greater than the said. Any confrontation with the abyss silences us. Life subjects us to trials, to many abysses. It is not easy for flesh and blood to dwell together.

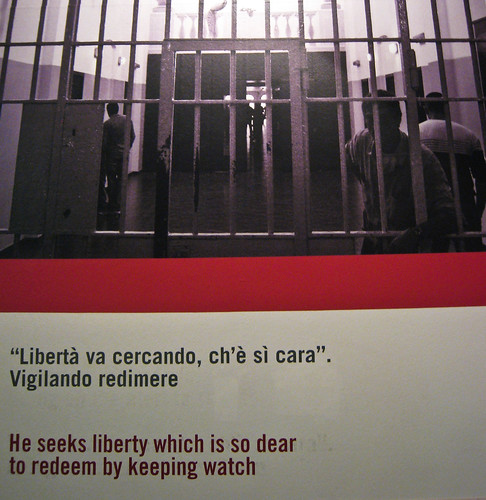

Fortunate favored me. I was fated to encounter the Hebrew language. It was in books for 2000 years and the Jewish people studied and prayed it, but didn't speak it. It came to life miraculously 70-80 years ago and I am a witness of its resurrection. So many years of silence are embedded in it, in every sentence. I who came from hell needed a primordial language to speak for me. The Bible taught me to contemplate, to feel the footsteps of life and to write. To write, to live only in what is necessary. Vigilantly to find silence that surrounds the written word. It taught me, but no one can write like the Bible. There is a powerful primordial nature in every page. No human being must imitate the writing engraved in stone, but the spirit of the Bible is open to everyone who is perplexed by the riddle of humanity and our life and to all who would express this world.

The Hebrew language opened my heart and connected me to my ancestors. When I came to Israel in 1946, a lost orphan, I could not imagine that the Hebrew language, not my mother tongue, would rehabilitate my great loss.