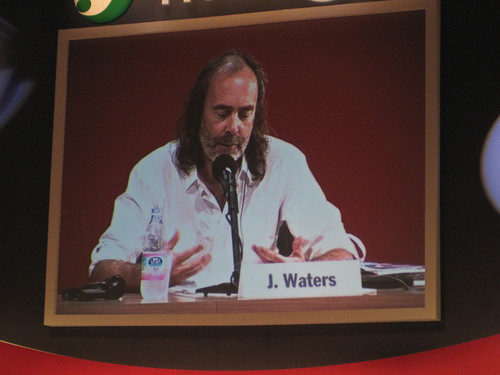

[Journalist John Waters shared the panel with Magdi Allam at the meeting to offer his contribution to the theme: "Protagonists or Nobodies?" As with Allam, coming to the Meeting was decisive in changing his way of looking at the world and of relating to it, as he showed in a story about his daughter. The following are my notes from his talk.]

He said sometimes he imagines a new phenomenon of meeting Jesus, as Andrew and John did, and how it might happen to him. If he were having coffee with a friend, and there was a spare chair, and what if someone sat down there. What exceptionality would it take for him to understand that this is Christ. He wonders how Christ would surprise him and what he would look like. He said it could happen, he doesn't rule it out. But for him the necessity is for an encounter in a cultural moment which is difficulty for all of us.

Our culture has effects on us which are not obvious. We look at reality and think we understand it and how it affects us. But this is not true. The culture is like a jungle that we encounter in the dark. We touch something, and we're not sure if it's a snake or a creeper, whether it's harmless or dangerous. We crawl about looking for signs.

We use the word "secular" to describe society. The word "secular" is an example of the problem. We think we understand it, but it may have no meaning or may be vague. It doesn't express the reality of the phenomenon. We need new words. Waters offered a word: "de-absolutization". The problem is not the decline of the power of churches or of religiosity, but what happens to me. The nutrients I need to survive are removed from the culture.

The question of the Gospel last Sunday from Jesus was who do you say that I am? Before this question, another question has to precede it [for each of us]: Who do I say that I am? How can I describe myself in society? How do I express the yearnings of my heart in a culture that is hostile in ways I don't understand?

On his journey, he was raised as an intense Catholic. But at age 20 he turned his back. Two years ago, he called himself a refugee from a misconception of freedom. He now calls himself a lapsed agnostic. For 20 years he pursued desires in resisting the society he grew up in. The phenomenon of alcoholism for him was a metaphor of society's pursuit of desire, of finding the limits of desire. It was not just a metaphor; he was actually drunk. It was an experience he could describe not as an excess of enjoyment but of his spirit seeking to escape his body and reaching out to a substance and imagining it had the answer. He described it as his soul emerging from his head. [Waters has a dry wit, but self-deprecating jokes don't transcribe well. Come next year to hear him!]

It's important to name the reality of what happens. The culture can give different explanations that appear plausible, which we take for granted. For example, we'll say the problem is psychiatric or a matter of the wrong desires. Another question is that conception of society of man as a machine. It is vital to understand the anatomy of the process of observing how I take for granted things in society as uncontroversial, and how these conceptions are actually inside me too.

In the myth of Narcissus man sees a reflection of himself and is changed. He sees himself as an object outside himself. This mirror is technology. Man creates technology, and it steals his humanity, there is a constant necessity to create new forms of technology. We have gone from the shovel and spade to the plow, tractor, to sitting in a combine harvester and listening to the radio. We can sit and watch the machines we created to do our work for us. It's a strange paradox. His uncles were strong men who worked with their hands. Waters himself writes on a machine and grows weak. So we have to invent a new machine to get strong again. We think this way, so we wake up and instead of having wonder at our own hands, we think: I must get coffee in this machine.

There are many example of things we take for granted, in addition to techology and machines. For example, we take opinion polls. We imagine that if we get the opinions of 50 people we know what everybody in this room is thinking. Why? In the 1930s Gallup discovered something that was true, how we are already fashioned by the ideology of society. It would be more natural to have a million different opinions and to find out what you think: shouldn't we ask you?

The language we use is constructed in such a way that permits me to speak the things that are permitted. It carries a logic that is destroying me. A new phrase we use to abolish the future is "going forward". Not, "I hope things get better" but "going forward" which implies I make the future from my dominion of reality. So the unpredictability of reality is destroyed in language. There are many examples of this.

In the public square, I can say only what is acceptable to say. A colleague of his from the Irish Times recently died of cancer. She spoke of her despair, her fear of death, that death was the end. She was asked two questions. The first was: is there an afterlife. She answered no. The second was whether she believed in God. She said it was a different question. And she spoke of the beauty of creation, art, life, all she hated to leave. She retreated back to say there is nothing. People praised her courage and honesty. For Waters, he thought it wasn't courageous or honest; she was articulate about her despair. She described perfectly, when she had nothing to lose, the abyss the culture has created for us. We conjure this abyss from fatalistic presumption, a joyless perception of ourselves. In the mirror we see hopelessness. Society speaks of progress and happiness, but imagines the worst possible scenario at the end for ourselves.

Recovering from alcoholism, Waters said, "I was an egomaniac with an inferiority complex". This is a way to describe our culture. We believe we create everything, that we are all-powerful, but we have no hope. What is the point? He sees, not because he is a prophet, but he sees in the eyes of others a correspondence to his own desire. The technical arena, the public square is ten years behind the human heart. Only in moments of blurting out do we recognize the truth. We usually sing in the harmony society gives to us. But sometimes someone or you strikes a different note, says something you didn't intend, then people look at you, is this permitted?

Patrick Cavanaugh, a poet, says the nature of poetry is not the words but what happens between the words, a flash of the absolute. The words are the least important thing when the poem is spoken.

As a child, Waters loved a beautiful Jesus, but thought he was an alternative to freedom. He had a choice between the beautiful Jesus and his freedom. He chose his freedom and was regretful. He had no quarrel with Jesus, though maybe with those who spoke for Him. He was so beautiful. He thought himself unworthy, or this was an alibi for the corruption of freedom. When Jesus is gone, he will enjoy himself.

Ian McEwan, in his novel On Chesil Beach, offers a beautiful and terrible description of an argument. Two people say things which are more than they intended, the process accelerates and becomes toxic. They separate. You see this from the internal dialogue. This is what happened to him and Christ. He talked himself into it. Even language sets off an explosion.

Heinrich Boll spoke of Havel who talks of reality beyond the horizon but does not mention God. This is out of courtesy to God whose name has been trampled by politicians, and not for lack of belief. Language is contaminated. So Waters welcomes the proposal of Giussani, who asks no more than that he be honest with himself, to engage and observe his reality.

After twenty years of crawling through the culture, he has come into the clearing. Like in McCarthy's The Road, there is a moment of recognition. People look at him like he hasn't been looked at before. Not piously, which would frighten him away. He needs to make a journey, clearly, logically, to be sure of everything. It would be easy to say yes. He sees Jesus there. But he has to be clear, to see everything. These people look at him this way. Or they don't look at him but at something in him he doesn't know is there, he looks behind himself. Like the character in Taxi Driver: "Are you talking to me?" And they are. They tell him to look at his life, his desire and experience. What does it tell you? Are you happy? No. So they invite him on a journey. He's inclined to turn away, but things happen to them and so he keeps on coming back. They excite curiosity which is bigger than him. They teach him things.

For example, Waters spoke with his 12 year old daughter the other day who was worried about a friend who was moving away. He told her love doesn't end, and that sometimes it is for the better, and not to be overwhelmed. After going to the talk by

Michael O'Brien, and hearing how O'Brien blessed his children in bed, as his father also did to Waters with holy water, he was touched. He remembered feeling the imprint of his father's fingernail a half hour later, even after the holy water had dried. Waters had never done this with his own children because of the impediments of the culture. Trying to kneel again, he found his knees wouldn't bend, as if the machine needed to be oiled. The most obvious thing he forgot to tell his daughter that morning and called her back. This is a 12 year old cosmologist who knows the stars well. He told her to speak to the One who knows all the stars. This is the Meeting, the only Meeting he knows of yet, He is there in his reality. He only has to open his eyes.