Tuesday, August 31, 2010

Hitch-22: The Last Revolution

Monday, November 3, 2008

Lazarus, Come Forth!

Bosnian-American Aleksandar Hemon, in his latest novel The Lazarus Project, offers a double story structure to suit his theme of dual citizenship. The narrator, Brik, is a a Bosnian expatriate and unemployed writer married to an American brain surgeon. To salvage his dignity, he has to publish a book. The pursuit of his subject, the 1908 killing of a Russian immigrant, Lazarus, by a policeman in Chicago, sets him on a journey across Eastern Europe. Brik (like Hemon) missed the Bosnian war, since he was in the U.S. when the shooting began and only heard the "steadily unreal rumors". He packs a load of survivor's guilt which gives rise to incessant questions.

Bosnian-American Aleksandar Hemon, in his latest novel The Lazarus Project, offers a double story structure to suit his theme of dual citizenship. The narrator, Brik, is a a Bosnian expatriate and unemployed writer married to an American brain surgeon. To salvage his dignity, he has to publish a book. The pursuit of his subject, the 1908 killing of a Russian immigrant, Lazarus, by a policeman in Chicago, sets him on a journey across Eastern Europe. Brik (like Hemon) missed the Bosnian war, since he was in the U.S. when the shooting began and only heard the "steadily unreal rumors". He packs a load of survivor's guilt which gives rise to incessant questions.The story lines are woven through alternating chapters. Lazarus was gunned down as a suspected anarchist, while his sister Olga was left to fend for herself against the hysteria and city interests, offering a parallel to the War on Terror. Brik is accompanied on his journey by his childhood friend Rora, a gambler, photographer veteran of the Bosnian war and an epic Old World figure. Rora is a storyteller in need of a scribe; he's also the opportunist, connected with warlords, who once sold "replica" chunks of the Berlin Wall and replaced prayers with native nursery rhymes as he led religious tours through Medjugorje collecting big tips. Rora offers a continual entertaining stream of stories but repels all questions. He has replaced questions with tales, as Brik will come to understand. Rora tells Brik he will never know anything.

Let me tell you what the problem is, Brik. Even if you knew what you want to know, you would still know nothing. You ask questions, you want to know more, but no matter how much more I tell you, you will never know anything. That's the problem.

Brik's wife Mary also resists questions. About death, when Brik asks if she ever gets angry, she answers: "When a patient dies ... I feel that he is dead." Mary won't acknowledge the mistakes America is making in the current war, which causes friction between them. He notes that her "hands are bloodied by love."

For Brik, religious observance has blocked the quest for truth. Mary and her family are Catholic, whereas Brik, when asked about his faith, answers ironically: "I am nothing... God knows God is no friend of mine.. I envy people who believe in that crap. They don't worry about the meaning of life and things, whereas I do."

As for ethics, he knows his own "moral waddling", sleeping late instead of working and with porn residing on his computer. He is "forever stuck in moral mediocrity" between Mary's high ground and Rora's nihilism. A journalist named Miller figures in both stories; as writers they cannot hold onto neutrality; in both cases they become implicated in the crimes.

Brik, seeing himself as a man who escaped with his life from a place of death, wonders why Lazarus would be resurrected only to continue wandering the earth. He wants to know: "Did the biblical Lazarus dream, locked in the clayey cave? Did he remember his life in death--all of it, every moment? ... Did he have to disremember his previous life and start from scratch, like an immigrant?" As he wanders through the graveyard of his grandfather's birthplace in the Ukraine, he chants: "Hoydee-ho, haydee-hi, all I want is not to die."

Brik confirms his unstated suspicion that all are implicated in the violence which recruits supposedly good people. After hiring a driver on their journey, he and Rora are used as an alibi for human trafficking. They rescue the girl involved, and in doing so Brik finds his own good intentions tested. By the end of the story, Brik will have a chance to sort through the events and stories, from his own and Rora's experience. He ends with the beginning, which is the intention to write, and what he will carry forward are these same questions.

Sunday, October 12, 2008

To Kill for Love

Chris is taking his friend and former colleague Larry on a duck-hunting trip. Larry will need some assistance, because the former college history professor has multiple sclerosis and less than a year to live. They once hunted together often, but this will be their last time, if Chris has his way.

Chris is taking his friend and former colleague Larry on a duck-hunting trip. Larry will need some assistance, because the former college history professor has multiple sclerosis and less than a year to live. They once hunted together often, but this will be their last time, if Chris has his way.Chris is divorced and in love with Larry's wife, Rachel. Larry, after losing his job, his body and periodically his mind to the illness, has expressed the wish to die. Chris plans to oblige him. This much you know practically from the first chapter of Jon Hassler's book The Love Hunter. Hassler, a Minnesota novelist, died last March of a Parkinson's-like illness.

Chris, a school psychologist, is not a criminal type by any ordinary standard. He can be careless: he nearly shot off his friend's head during their first hunting expedition. He was responsible for his ex-wife's dog getting killed in traffic, though he has a good explanation for it.

Rachel (for the most part) and their son Bruce are devoted to Larry in his illness. Her relationship with Larry's best friend is complicated. Larry needs Chris, but Chris' attentions toward Rachel strain Larry's already fragile mental state. Rachel, an actress, keeps Chris guessing. He figures once Larry is out of the way the problem will be solved.

The book is a dialogue on love, and Chris and Rachel have different theories. Rachel sees a continuity between what her husband was and what he is by now with love as the constant. Chris, who admits to his emptiness, sees love as a blind attraction.

Love, according to Chris, was that heedless dash toward what we believe is the source of our happiness, never mind if the source proves, when we get there, to be nothing but a squawk box.The details of the story are precious. This is a messy illness, and Larry's grief is harrowing. Chris wants to keep things in hand, but events never go according to plan. And life itself will intervene in a very satisfying manner.

Wednesday, August 27, 2008

Aharon Appelfeld at Rimini

[A few months ago, I posted a quote from Traces from an interview with the Israeli writer and Holocaust survivor Aharon Appelfeld. I was very fortunate to hear him speak at Rimini yesterday and transcribe my notes below in first person. The title of the talk was "Bellezza e positività della vita" or "Beauty and Positivity of Life". He gave a very poetic and deliberate delivery, so I reproduce it as closely as possible.]

I refer to my generation, 1939'44, to children condemned to death. I was born in 1932 in Chernowitz in Eastern Europe which was Jewish and assimilated. My parents thought of themselves as European. My grandparents followed the Jewish commandments but without belief. They couldn't change their way of life. They had a sadness that was one of defeat.

The Holocaust buried us in suffering without distinction between believer and the alienated. Our suffering was physical as children, we had no soul-searching. For our parents, it was the loss of the world, their beliefs were overthrown. We were left only with naked Jewishness. It was an empty loss. Tens of thousands of Jews were separated from dear ones, deprived of everything, stigmatized with shame. Their heritage hemmed them in, blocked the path to full freedom. Together Jews from East and West were under an iron sky.

We were first exiled to the railroad station, with an enormous panic of hunger and crushed. We absorbed our parents' bitter silence before our separation. Our parents protected us until the last moment when they left us, as Moses' mother left her baby to the mercy of heaven.

Loneliness was our lot. Some were in the forest, others in monasteries and others lived with tyrannical peasants who treated us like beasts. We learned the secret of Judaism. It's better to hide it. Those with no parents were isolated from humanity and grew up like animals, cold and fearful. Judaism made us fair game. Without it, existence is more meager. That secret was the only shelter over our misery. We had images of our parents and our homes, our last refuge.

We lived with death as familiar but not ceasing to be afraid. Every encounter with death increased our fear. The promise to our parents was that we would look out for ourselves. This made us stronger than we were, when we wandered from forest to forest. We were not children but animals, who are lost in the dark thickets of forest. We learned to get food from trees, fire from stones and to reflect.

Why were we so persecuted? In the woods and on riverbanks, that question arose in all its nakedness. We thought it was our smell, our longer ears, our fear of darkness. If we overcame our flaws, no one would guess we were Jews. We did not know that was the old Jewish curst passed on.

In 1945 at the end of the war, I was 13. What to do, where to go? There was a sea of refugees flowing from place to place. We had a huge debt and didn't know where to put it down and get rid of it. A great catastrophe leaves us mute. What can we say about the death of one person, what more a heap of corpses. Speech was blocked, almost nothing was said. Speech is to serve existential needs, approaches the depths of the soul, is metaphysical. It is silent. The depths are full. Appropriate vessels were not raised up for what had accumulated.

I was orphaned not only from my parents, but their values and beliefs seemed naive and ridiculous in the face of the monstrous people who tortured us. What would our world be from now on? To go into the pit of cynicism, betray the beliefs of our parents, to betray the faith of my grandparents, inward religiosity, betraying my communist uncles who had sacrificed life for the redemption of humanity.

One dark evening, I realized the ghetto, camps, and forests would never leave me. I was lost in a world of lost values. I wrote the names of my parents, grandparents, uncles, cousins on a piece of cardboard. I wanted to make certain that they had existed, that the house I came from was not imaginary. By writing their names, I brought them to life. They rose and stood before my eyes.

I was no longer an orphan but a boy surrounded by loving people. I was so happy, I kept the paper in the lining of my coat, the key to my chest, precious secrets of the soul. If I felt lonely or oppressed, I took out the cardboard, the real names of the parents I had lost.

Writing opens a hidden world. The written word has the power to kindle imagination and illuminate the self. From cardboard to writing took a long time. Everything revealed in the war years crowded in me like a dark mass. I thouhgt of the ghetto, camp, forest. The images were no less horrible than reality. To avoid images, I would run out to cut myself off from them. The method worked only partially.

The past can't easily be separated from you. In 1946 in Palestine there was a pioneering spirit to create a new Jew, to shed the dread of the past. To turn toward the present and the future. The Jewish past was a curse to escape. The experience of the past seemed something shameful to be erased. Go and uproot from the soul everything experienced from five years to plant a pastoral idea. Forget about that significant part of life. People did that with a heavy price. A person without a past, as dreadful and shameful as it may be, is handicapped without connection to parents, grandparents. Without the values instilled by ancestors, it is like being a living body without a soul.

I wrote letters to my mother at night. It was a collection of trivial details about daily life. If they reached, her, they would make her happy. I did it eagerly night after night, which connected me to the world once mine. It did not act like a magic wand. Vexing questions plagued me. Who was I? What was I doing in an agricultural training program at the edge of the desert? Could I deny the spiritual world? My mother tongue was German. I heard it ag home until age 9. I learned Lithuanian and Prussian during the war. A few German words were sufficient to write to my mother letters full of mistakes.

In the afternoon I studied the Hebrew of daily life and the Bible. A young man from an assimilated, secular home recoils against religious books. I was not familiar with the Hebrew Bible and thought it full of angels and saints. What did they mean to me? A surprise awaited me. The patriarchs of the Bible were not saints but earthly, lively. There were treasures stored in the Bible. I decided to copy a chapter every day.

The Hebrew Bible deals not only with content but with form. The whole enchanted me. Biblical prose is simple, unembellished, lacking description, almost without adjectives. Like all ancient languages, it has a severity, a hard logic without sentimentality. I didnàt know severity suited my life experience. On the suffering of ghetto, camp, forest, it is impossible to lavish words. The greater the suffering, the more important it is to use few words. Pain refuses to be shaped by a language drunk with words.

In Biblical prose not speaking is as important as speech. Outward description is an illusion. We must strive to reach the inner kernel of soul. I didnàt internalize this easily or rapidly. The attraction for the sentimental or the noisy is almost natural. Biblical prose taught me to overcome the tendency the victim to regard himself as always right. Biblical prose taught me an objectivity to the superficiality of one-sidedness. In my life experience, egocentrism lurks in every corner.

Biblical narrative has no ideal people. These are flesh and blood with weaknesses. One is a womanizer, another vengeful, one sends a man to battle to die to take his wife, another is a villain. Primo Levi, on writing of Auschwitz, also wrote in very factual, dry language without rhetorical ornament, perhaps for the same reason.

It took great effort to acquire the Hebrew language. I made it my mother tongue and language to find me to my grandparents and great-grandparents and to learn about the character and destiny of the Jews. I read and copied the Bible. It included various experiences--poetry, prophecy, law, history, philosophy. I was charmed by narrative - people emerged, earthly people, but connected with heaven. There were no saints among them. But they knew in their souls they would not be without answers.

I read the Bible with devotion but it wasn't especially religious reading. I wanted to cling to the roots of language, to the primal experience of stories. It was a great joy, after years of struggling, I wrote a short story. The content was not biblical, but there was something of the poetics of the Bible in it.

Poetry is the assertion of strong people in the world, conscious and unconscious, people with us and those who have passed away. The longings, fears, grief and despair, marvelous moments. Life raises us beyond ourselves. We feel closeness to God. The Bible story has earnestness, like prayer, enclosed within it, it opens the heart in spiritual accounting. It does not lack humor, irony, penetrating criticism, ambiguity and sarcasm. The Biblical narrative is not didactic. It deals with good and evil, obligations, devotion, love for unworldly purposes and love for its own sake without preaching or idealization.

The Biblical narrative teaches that man is dust and ashes and created in God's image, two powerful feelings that traverse the length and breadth of the Bible story. Though heroes of the Bible forget, they are created in God's image. They behave like fatalists addicted to eat, drink and be merry for they will die. Abraham has closeness to God, is intimat ewith revelations, but has moments of weakness. He claims his wife is his sister for fear Pharoah will kill him. His treatment of his wife, of Hagar, is far from splendid.

The Bible shows human beings with lives and tribulations, with great questions on the purpose of our lives. It is great literature to be judged by what and by how. A true statement can sound false, banal, arrogant, garrulous if it doesn't find the correct form.

The story of the sacrifice of Isaac, what absurdity, cruelty, how can it be submitted without discussion? A short harrowing episode riddled with silence. What can the father say to the son? There is a short dialogue between them which is less revelatory than perplexing. Before the abyss our jaws are dropped. What lesson from this trial? Do everything God commands you, even if contrary to feelings of humanity. Any lesson from the episode, subject to a trial beyond comprehension, would be narrow-minded, dogmatic. Silence rather than speech characterizes it-the unsaid is greater than the said. Any confrontation with the abyss silences us. Life subjects us to trials, to many abysses. It is not easy for flesh and blood to dwell together.

Fortunate favored me. I was fated to encounter the Hebrew language. It was in books for 2000 years and the Jewish people studied and prayed it, but didn't speak it. It came to life miraculously 70-80 years ago and I am a witness of its resurrection. So many years of silence are embedded in it, in every sentence. I who came from hell needed a primordial language to speak for me. The Bible taught me to contemplate, to feel the footsteps of life and to write. To write, to live only in what is necessary. Vigilantly to find silence that surrounds the written word. It taught me, but no one can write like the Bible. There is a powerful primordial nature in every page. No human being must imitate the writing engraved in stone, but the spirit of the Bible is open to everyone who is perplexed by the riddle of humanity and our life and to all who would express this world.

The Hebrew language opened my heart and connected me to my ancestors. When I came to Israel in 1946, a lost orphan, I could not imagine that the Hebrew language, not my mother tongue, would rehabilitate my great loss.

Tuesday, August 26, 2008

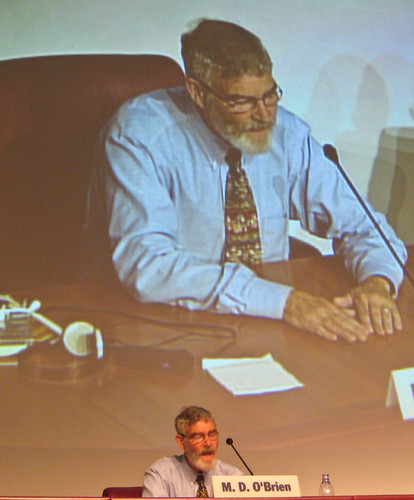

Michael O'Brien at Meeting 2008

I had to fight my way into the first conference at the Meeting 2008 at Rimini by name-dropping (Letizia Bardazzi, remember that!), so instead of standing at the back, I landed a second-row center seat! The hall was already filled with hundreds of people waiting to meet Michael O'Brien, the Canadian author of Father Elijah (which has been translated into eight languages) and some half-dozen more titles published by Ignatius Press.

The unassuming father of eight didn't come to speak about his books, however, but instead addressed the subject of fatherhood and particularly of God our Father, and of his silence which is total presence to us with an immense love.

O'Brien quoted from then Cardinal Ratzinger's address in Palermo in 2000 who offered an urgent message on fatherhood.

Human fatherhood gives us an anticipation of what God is. But when human fatherhood does not exist, when it is experienced only as a biological phenomenon without its human or spiritual dimensions, all statements about God the Father are empty. That is why the crisis of fatherhood we are living in today is an element, perhaps the most important, threatening man in his humanity.

Ratzinger then reflected on the name of God, because God is a Person and has a Name. In the Apocalypse, God's antagonist, the Anti-Christ, is a Beast. He has no name, but a number. In the concentration camps of World War II, faces and names were erased. People were transformed into numbers. This is the spirit of the anti-Christ, to make man a component of the meta-machine, to be reduced only to a function. The anti-Christ makes war on mankind.

In our days, Cardinal Ratzinger warned, we must not forget the monstrosities of history which occur when we adopt the same mentality. The world of the machine becomes normal. The machine imposes the same law as the concentration camp when men are interpreted by a computer, translated into numbers.

God our Father has a name. He calls each of us by name. He is a person who looks at us and sees another person. The true story of man is that we are sons and daughters, and we can never be things. To be a thing is the working definition of materialism, of a soft totalitarianism.

This is homo-sino-deo, man without God, autonomous man. Some have never known a Father, are orphaned, or think they never had a Father. The problem is multidimensional: social, psychological, spiritual.

O'Brien went on to relate three personal stories from his experience as a father which I won't transcribe because too much would be lost without his own delivery. The impression left was of a strong man of faith who encouraged us to trust in God's paternal love for each of us and to accept the sacrifice united to the cross that love needs to expand the heart.

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

Obedience and authority in Luigi Giussani's trilogy

Again, it is very interesting to note that "authority" does not occur in the index to At the Origin of the Christian Claim, and "obedience" makes its first appearance, but only shows up twice in this book. In the first instance, Fr. Giussani is recounting a dramatic event, recorded in chapter 8 of the Gospel of John. Jesus has been confronted by the Pharisees, who press him to explain who he claims to be. Jesus responds, "If I glorify myself, my glory is nothing; it is my Father who glorifies me, of whom you say that he is your God. But you have not known him; I know him. If I said, I do not know him, I should be a liar like you; but I do know him and I keep his word" (John 8:54-55). Fr. Giussani doesn't refer directly to Jesus' obedience, but quotes from the work of two scholars, R. Schnackenburg and H.U. von Balthasar, who use this word to characterize Jesus' attitude. Balthasar comments, "the attack on Jesus' arrogance collapses on his obedience" (The Glory of the Lord, page 478). The only time in At the Origin of the Christian Claim when Fr. Giussani uses the word "obedience" himself comes toward the end of the book, in a discussion of the value of the human person. He characterizes Jesus as demonstrating, "a passion for the individual, an urgent desire for his happiness." Jesus expresses, "The problem of the world's existence is the happiness of each single person. 'For what will it profit a man, if he gains the whole world and forfeits his life? Or what shall a man give in return for his life?' (Matthew 16:26)" (page 84, in At the Origin...). Fr. Giussani concludes, "No force of energy and no paternal or maternal loving tenderness has ever impacted the heart of man more than these words of Christ, impassioned as he is about the life of man. Moreover, to listen to these radical questions Jesus poses, represents the first obedience to our own natures" (page 84, emphasis mine). Thus, even before introducing the idea of obedience to authority, Fr. Giussani first stresses Christ's own obedience to the Father, and with even greater emphasis, our need to be obedient to our own natures and irreducible value. I think these points are fundamental, and cannot be skipped over or forgotten. This type of obedience is an essential step; without it, we are not capable of obedience to authority.

Can you guess where Fr. Giussani first begins to speak about authority? Not until we are a good three quarters of the way into Why the Church? do we find a discussion of the subject. Authority, Fr. Giussani stresses, is a function of the life of the community: "The supreme authority of the magisterium is an explication of the conscience of the entire community as guided by Christ. It is not some magical, despotic substitution for it" (page 172). Then he goes on to discuss the Church's teaching authority, pointing out that even in the case of the dogmas that seem to have come down from "on high," in fact, in every case (The Assumption, The Immaculate Conception, papal infallibility), they are the fruit of the whole community; debated, voted upon, and tested, these dogmas were not proclaimed until the popes had come to the firm conclusion that the entire community's conscience had been sounded. Fr. Giussani observes, "Clearly, then, the vast majority of people have no idea of the Church's procedure leading to the proclamation of a dogma, never mind comprehending the meaning of the expression. But, as we have seen, it defines a value when that value has become a sure and living part of the conscience of the Christian community" (page 174). In other words, the Church's teaching authority derives from its unity (and consistency). This is a very different picture from the one conjured by the term, "authoritarian." Then, in the final chapter of Why the Church? Fr Giussani returns to the question of authority. If the Church's catholicity, that is its universality and unity, is a sign of its authority within space, then her apostolicity "is the characteristic of the Church which signified its capacity to address time in a unitary, structured way" (page 230). Then he says something that is really worth pausing over: "...Just as Christ's will was to bind his work and his presence in the world to the apostles and in doing so he indicated one of them as the authoritative point of reference, so, too, is the Church bound to Peter's and the apostles' successors -- the pope and his bishops" (230). Jesus stooped to bind his work and presence to particular persons (colorful, even sometimes idiotic persons!), and the Body of Christ makes the same gesture, in obedience to its own nature. There is a beautiful and audacious symmetry in this thought! For the Body of Christ to fill time and space, in order to be truly "all in all," then it teaches what is true for all (preserving its catholicity/universality) and it remains faithful to Christ's original method, to bind itself to a particular succession of persons, who become its authoritative point of reference (preserving its definitive presence in time). The concept of obedience to the Church also makes a brief appearance in this book on page 86 and is worth quoting at length:

Christians are often far from aware of this authentic source of their value, for we frequently find people who are either seeking clarity and security or a motive for their actions, and in so doing, they interpret their own community, or movement, or special association in a reductive way, depriving themselves of the source of unity that gives them life -- the mystery of the Church as Church. Or, there are those who in referring to the Church, mean a mechanical super-organism unrelated to their daily reality, the concrete community close to them. In this way, then they incorrectly separate themselves from the living Church. This is why one must learn what the total Church is, and this is why we must explore the depths of the ecclesiastical experience one has encountered, providing that is has all the characteristics of a true ecclesiastical experience. This means obedience to the total Church, depending on it, organizing one's life according to its rhythms, seeing oneself reflected in the other factors within the sphere of the Christian life. These are aspects which define the validity of gathering together...Far from recommending "blind obedience," Fr. Giussani is urging us to adhere to "the total Church" in order to assure that our gatherings are invested with the life of Christ.

We have thus demonstrated how reflection on the word "ecclesia" has helped us to understand the type of consciousness of the first Christians of the value of their community, a value which derived totally, entirely from participation in the one Church, the Church governed by the apostles. (pages 86-87, emphasis mine)

Sunday, April 27, 2008

Thanatos Syndrome: book of the month

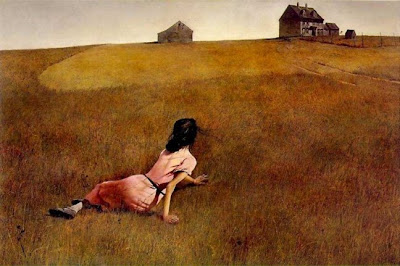

«All at once she became afraid. She was afraid of people, places, things, dogs, the car; afraid to go out of her house, afraid of nothing at all. There are names for her disorder, of course — agoraphobia, free-floating anxiety — but they don't help much. What to do with herself? She did some painting, not very good, of swamps, cypresses, bayous, Spanish moss, egrets, and such. I thought of her as a homebound Emily Dickinson, but when I saw her on the couch in my office — she had made the supreme effort, gotten in her car, and driven to town — she looked more like Christina in Wyeth's painting, facing the window, back turned to me, hip making an angle, thin arm raised in a gesture of longing, a yearning toward — toward what?

In her case, the yearning was simple, deceptively simple. If only she could be back at her grandmother's farm in Vermont, where as a young girl she had been happy.

She had a recurring dream. Hardly a session went by without her mentioning it. It was worth working on. She was in the cellar of her grandmother's farmhouse, where there was a certain smell which she associated with the "winter apples" stored down there and a view through the high dusty windows of the green hills. Though she was always alone in the dream, there was the conviction that she was waiting for something. For what? A visitor. A visitor was coming and would tell her a secret. It was something to work with. What was she, her visitor-self, trying to tell her solitary cellar-bound self? What part of herself was the deep winter- apple- bound self? What part of her was the deep winter- apple- bound cellar? The green hills? She was not sure, but she felt better. She was able to leave the house, not to take up golf or bridge with the country-club ladies, but to go abroad to paint, to meadows and bayous. Her painting got better. Her egrets began to look less like Audubon's elegant dead birds than like ghosts in the swamp.»Walker Percy, The Thanatos Syndrome, p 4

Such is the earliest sign in Percy's bestselling thriller about Dr. Tom More. Having been absent for two years from Feliciana County, Louisiana, Dr. More is puzzled to discover that this case study's problem has evaporated without a trace. Instead, she is chipper and unproblematic.